A man lights fireworks during a traditional ceremony to ask for rain and good harvests in a remote community of Michoacán. In a region marked by violence and state abandonment, local residents and community guards gather to protect the ceremony and ensure it can take place in peace, preserving cultural practices amid ongoing conflict.

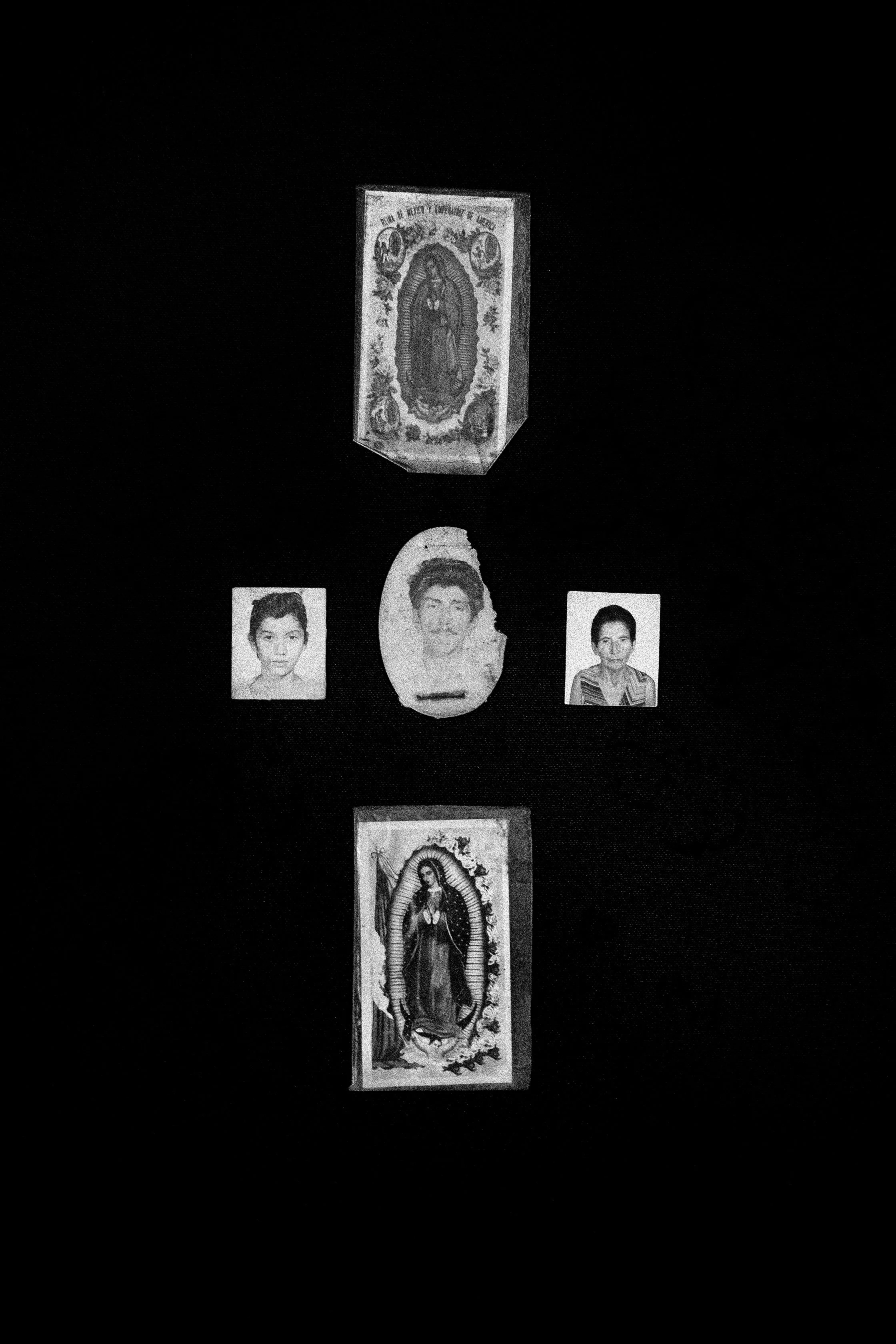

The most cherished belongings of a migrant named Jesús Velázquez, who fled his hometown in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, due to violence and death threats from organized crime groups, are displayed at the U.S. border. The objects include photographs of his sister, and of his father and grandmother who died six years ago. Velázquez says he believes the people in the pictures are watching over him during his journey to the United States.

Residents of El Alcozacán, Guerrero, perform a ritual to ask for rain and fertile harvests. Since 2020, the community has lived under threat from criminal groups and armed attacks, facing forced displacement, killings, and state abandonment. In this context, preserving their traditions has become a quiet act of resistance and a defense of their identity.

Children from El Alcozacán, Guerrero, protest to demand their right not to be recruited by self-defense groups like the CRAC-PF nor to bear arms. In the region, these groups have begun recruiting minors to confront drug cartels, putting their childhood and future at risk. This phenomenon has been documented on several occasions, especially in communities such as Ayahualtempa, Tlapa, and Chilapa, where minors join self-defense groups to protect themselves from violence. Some children do so voluntarily, motivated by the desire to protect their families. This protest, which took place a few days before Children’s Day, is a cry of resistance against violence and forced recruitment. The children, dressed in festive attire for a traditional dance, demand to be heard and to live a childhood free from weapons and war.

Residents of El Alcozacán, Guerrero, perform a ritual to ask for rain and fertile harvests. Since 2020, the community has lived under threat from criminal groups and armed attacks, facing forced displacement, killings, and state abandonment. In this context, preserving their traditions has become a quiet act of resistance and a defense of their identity.

In Acatlán, Guerrero, a mountainous region affected by insecurity and limited state presence, residents take part in ritual fights to ask for rain and good harvests. According to tradition, every drop of blood shed is answered by a drop of rain. Amid violence and abandonment, these ancestral ceremonies endure as acts of resilience and a reaffirmation of the community’s bond with the land.

A recently harvested cornfield in Alcozacán, Guerrero, a region affected by violence and displacement

Members of the CRAC-PF patrol the streets of El Alcozacán, Guerrero, during the traditional ceremony to ask for rain and good harvests. In a region marked by violence and state abandonment, their presence aims to protect the community and ensure the celebrations can take place in peace.

Adán shows the bullet wound on his hand, sustained during a clash with the criminal group Los Ardillos in El Alcozacán, Guerrero. Like many in his community, Adán is part of the self-defense forces that emerged in response to the lack of state protection. His injury reflects not only the violence gripping the region but also the daily struggle to survive and defend their land.

View of the border in Tijuana, where the wall separates Mexico and the United States. In View of the border in Tijuana, where the wall separates Mexico and the United States. In 2025, thousands of migrants continue to wait due to Trump-era immigration policies like the "Remain in Mexico" program. Shelters in the city are hosting fewer people than before, but conditions remain difficult. The migration route remains one of the most dangerous in the world, posing serious risks for those attempting to cross.

Paramedics assist a man after he was injured during a robbery in Tijuana, a city where violence and insecurity remain persistent challenges

A woman injects heroin into her neck at a shooting gallery next to the wastewater canal in Tijuana, Mexico. The city has seen a rise in drug use and public health challenges amid ongoing migration and insecurity.

A Christian association assists a person who uses drugs under a bridge along the sewage canal in Tijuana, treating arm infections caused by intravenous drug use. The spread of fentanyl has worsened the public health crisis along the border, increasing overdoses and infections among vulnerable communities.

Germán, a drug addict who lost his arm due to substance abuse, bathes in a sewage canal in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. According to the Baja California Citizen Security Observatory, more than 17,000 people live on the streets of Tijuana, many struggling with addiction and mental health issues in areas with little to no access to basic services.

Paramedics from the Mexican Red Cross and federal police officers confirm the death of a man who was shot outside his home, in a country where high levels of violence remain a major concern.

Portrait of our colleague, Margarito Martínez Esquivel, a journalist and photographer for Semanario Zeta, who was murdered in Tijuana, Baja California, on January 17, 2022. Known for his reporting on organized crime, his death highlights the risks journalists face in Mexico.

A man lies dead by the roadside in Tijuana, Baja California, while another records the incident on his phone. The photo, taken in 2020, reflects the ongoing insecurity in the city, where violence linked to organized crime continues to impact daily life.

Members of Mexico’s SEDENA (Secretariat of National Defense) take photos in Tijuana, Baja California, as a seized drug shipment burns during an operation. Such actions are part of ongoing efforts to combat drug trafficking along the northern border.

A man wearing a shirt featuring Jesús Malverde carries a figurine of Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán in Sinaloa. The figurine reflects the admiration some have for the notorious drug lord, seen by some as a symbol of power and defiance, despite his criminal legacy. Jesús Malverde, revered by many as the "narco-saint" and protector of the poor, is often venerated alongside figures like Guzmán, viewed by some as a symbol of resistance against authority.

Men pose with figures of Santa Muerte in Tepito, a working-class neighborhood in Mexico City. Venerated as a protector and symbol of justice, Santa Muerte has gained followers among informal workers, migrants, prisoners, police officers, and communities affected by violence. Her cult has grown in response to insecurity, poverty, and distrust in institutions.

Portrait of Hermenegilda, outside the Mercado de Sonora, Mexico City, January 2025. where items related to santería, esotericism, and traditional medicine are sold, frequented by those seeking spiritual protection and healing.

Jesús, a 25-year-old funeral home employee, lies inside a coffin during his shift at a funeral home in Tijuana, Mexico. The city has consistently ranked among the most violent in the world, with more than 2,000 homicides reported annually in recent years.

My grandmother Estela Millan, lies inside her coffin during her funeral in Guanajuato, Mexico.

A devotee of Santa Muerte purifies figurines of the folk saint with Cuban cigar smoke during a ritual in Mexico City. Worship of Santa Muerte, often associated with protection and guidance, has grown among marginalized communities seeking comfort amid violence and insecurity.

A devotee of La Santa Muerte walks on her knees toward the pottery altar during the first of the month in Tepito, a neighborhood in Mexico City known for its connection to popular spiritual practices. La Santa Muerte, often depicted as a skeletal figure, is venerated by many, especially in marginalized communities, as a protector and symbol of justice. The ritual is part of a broader tradition that blends Catholicism with indigenous beliefs, offering solace to those seeking protection or answers in a world marked by insecurity and hardship.

(L) A masked armed man adjusts his balaclava at an informal checkpoint operated by civilians near El Limoncito, in Michoacán, Mexico. (R) A trophy abandoned in a local school reflects the disruption caused by ongoing cartel violence. Once known for its agricultural productivity, the region has been severely affected by clashes between vigilante groups and criminal organizations, leading to widespread displacement. Nearby communities like El Aguaje have been largely deserted, as residents flee threats and violence linked to organized crime.

View of belongings and furniture in an abandoned house in El Limoncito, Michoacán. These empty structures stand as silent witnesses to the violence and forced displacement caused by organized crime in the region. What were once homes of prosperous families are now deserted spaces, the result of threats from criminal groups. The town, along with El Aguaje, has experienced significant depopulation due to cartel violence, leaving behind these remnants of a community marked by crisis.

Exterior view of a house taken over by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel in El Aguaje, Michoacán. The abandoned home reflects the forced displacement of entire communities amid escalating cartel violence. In this region, houses and streets have been overtaken by armed groups, leaving behind a landscape marked by fear, silence, and the absence of those who once lived there.

(L) An image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, riddled with bullet holes, stands near the entrance of a burned and looted home following an armed clash between rival cartels in El Limoncito, Michoacán. Like many towns in the region, it has been largely abandoned as violence and forced displacement drive residents away. (R) A figure of Santa Muerte stands in the living room of a house taken over by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) in El Aguaje, Michoacán. The area remains deeply scarred by cartel violence and ongoing territorial disputes.

Portrait of Dacia Evelin, 11, originally from the state of Michoacán, at migrant shelter in Tijuana, Mexico. The most treasured belonging of Dacia Evelin, her backpack, lies on the ground at a migrant shelter in Tijuana, Mexico. “Cartels were fighting for territory — you can imagine why we left,” says her mother, Marisol Espino. Dacia, who loves studying and excels at math, insisted on bringing her backpack when the family fled Michoacán in December 2022 to seek asylum in the United States.

Donde díos es ciego (Where God Is Blind)

This project shows how pain, faith, and everyday life come together in Mexico. It doesn’t try to show violence as something distant, but as a presence that has entered our homes, our routines, and the way we live.

It speaks of a country where death has become part of the landscape, where people keep going despite the fear. The images don’t show horror, but how we continue living within it — how faith, memory, and life mix together.

I want to look at what remains, the small gestures that allow us to keep going, even when it hurts. Because to speak of violence without romanticizing it is also to speak of humanity without idealizing it.